Martin Bunzl taught Philosophy at Rutgers for 40 years before retiring. Philosophy is a hard taskmaster – you can spend a lifetime thinking about a problem and hope to make incremental progress in clarifying what is going on, even if you can’t solve it. Frustrating as that may seem, to me, it has been a privilege to be paid to spend my days just thinking. His recent work lies at the intersection of philosophy and the environment, with a special interest in climate change.

Martin Bunzl taught Philosophy at Rutgers for 40 years before retiring. Philosophy is a hard taskmaster – you can spend a lifetime thinking about a problem and hope to make incremental progress in clarifying what is going on, even if you can’t solve it. Frustrating as that may seem, to me, it has been a privilege to be paid to spend my days just thinking. His recent work lies at the intersection of philosophy and the environment, with a special interest in climate change.

Martin is interested in both questions of risk and questions of responsibility. Risk, when it comes to uncertainty about how what we do may produce catastrophic outcomes. Responsibility, when it comes to understanding our duty to do no harm without it being clear to whom, or to what, we have that duty. He blogs about these and other issues of pressing concern at www.mbunzl.com which also provides information about other areas of his research.

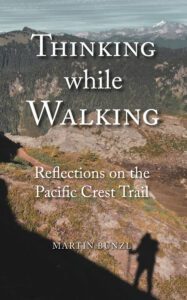

Martin’s just-published book, Thinking while Walking: Reflections on the Pacific Crest Trail, is an invitation for the reader to walk sections of the trail from the Mexican border to the Canadian border with him and think about everything from the mundane (what makes litter litter) to the profound (how to make sense of our duty to nature). Throughout the book, Martin comes back to one theme in one way or another – the “constructed” idea of ‘nature’ as a romantic ideal that blinds us to our role in shaping the world since we established settled agriculture thousands of years ago.

Martin is especially interested in the way that creates a false binary in responding to the climate crisis between the ‘natural’ and the ‘artificial’. He is also interested in the way our romantic conception of nature constitutes a rich society’s privilege that ignores what we need to do to ensure the wellbeing of all people in the world.

BELOW IS AN EXTRACT FROM MARTIN’S BOOK ‘THINKING WHILE WALKING’.

~ ~ ~

By the time you reach Rainy Pass, you are immersed in the wildness of the Northern Cascades surrounded by, what a guidebook describes as, numerous tightly ordered rings of conifer-clad mountain ranges. This is nature in which the uniformity of the flora restrains the variation of the geology and allows you to be sensitive to minor differences in your surroundings. The effect over time is mesmerizing. I stop, overwhelmed, moved to tears. To me, it is perhaps the most stunning part of all of the Pacific Coast Trail. It is at once both wild and intimate at the same time.

Because I am a cynic and a realist about natural selection, I understand that nature achieved this overpowering beauty by accident. But that does not stop me from wondering about that beauty, even if it was not created by design to be beautiful. How am I to understand it, and my relationship to it?

There is a simple answer to this question that I am desperate to avoid: the beauty we find in nature is something we bring to nature. It does not exist independent of us. And as with beauty, so to0 with all other values in nature. As such, if that is the case, the importance of conserving beauty in nature is attenuated, and were we to come to disvalue it, we do nothing wrong – except insofar as we wrong ourselves. We may wrong ourselves by misrepresenting what we value to ourselves. Or may do so by misrepresenting what our descendants may value. But we have no obligation except to ourselves and each other.

Maybe that obligation to ourselves and each other is robust enough to guarantee that we will care for the world, even if the record of our behavior so far does not inspire confidence in that conclusion. But even if it did, I yearn for something stronger. I want an account of the value of nature that does not depend on us. Indeed, I’d like an account of that value of nature that creates a duty in us to care and protect it, irrespective of our self-interest. But I have come to think of this fixation on duty and obligation as misconceived. Better I think to focus on a very different value: humility.

To be on the Trail in the Northern Cascades is to be overcome with a sense of awe, a sense of nature’s grandeur, and a sense of how small and insignificant we are compared to it. That sense is the essence of the experience of humility and humility begets respect. In his dissertation, Joshua Weinstein argues this notion of humility is not the notion deployed in the Judeo-Christian tradition, but it is in other (Eastern) religious traditions:

[T]he Western tradition sees humility, and its identification with the Earth, the ground, as abasing, implying lowliness, and meekness, and low self-opinion. From Western religious and spiritual perspectives, this abasement is seen as positive in that it serves, in one way or another, to place humans in an appropriate relation with …G-d [God].

On the other hand:

The ideas of respect and compassion here are fundamental to understanding an Eastern tradition of humility. Whereas the Western tradition of religious humility tends to focus on a dichotomy of man / low and G-d/ high, with man submitting to the power of an Almighty G-d, the Eastern tradition of humility is framed more in terms of respect and compassion, rather than power or submission.

If I have been too quick to embrace the search for a foundation for our obligation to nature, I need to avoid thinking we have an obligation to be humble in the face of nature. Instead, perhaps we should forgo the aspirations of a philosophical argument in favor of a psychological argument that begins with our experience of nature.

Speaking of Yellowstone Park, Theodore Roosevelt declared “This Park was created and is now administered, for the benefit and enjoyment of the people… .” But I think this gives short shrift to what makes the national parks so important. It is not that our enjoyment of them does not matter, but that that pales in importance to the effect that they have on us. Instead of arguing that we should bring a sense of humility to our experience of nature, we should accept that our experience of nature evokes a sense of humility in us that has the capacity to ramify to all other areas of our lives without a need for justification.

This idea, that we should expose ourselves to what in nature will cultivate our better selves, is part of a more general idea in favor of the virtues of moral psychology over moral philosophy. Instead of trying to discover a foundational argument as to why we should be moral, we should seek the experience that which will evoke a moral response in us and thereby nurture the development of our moral characters.